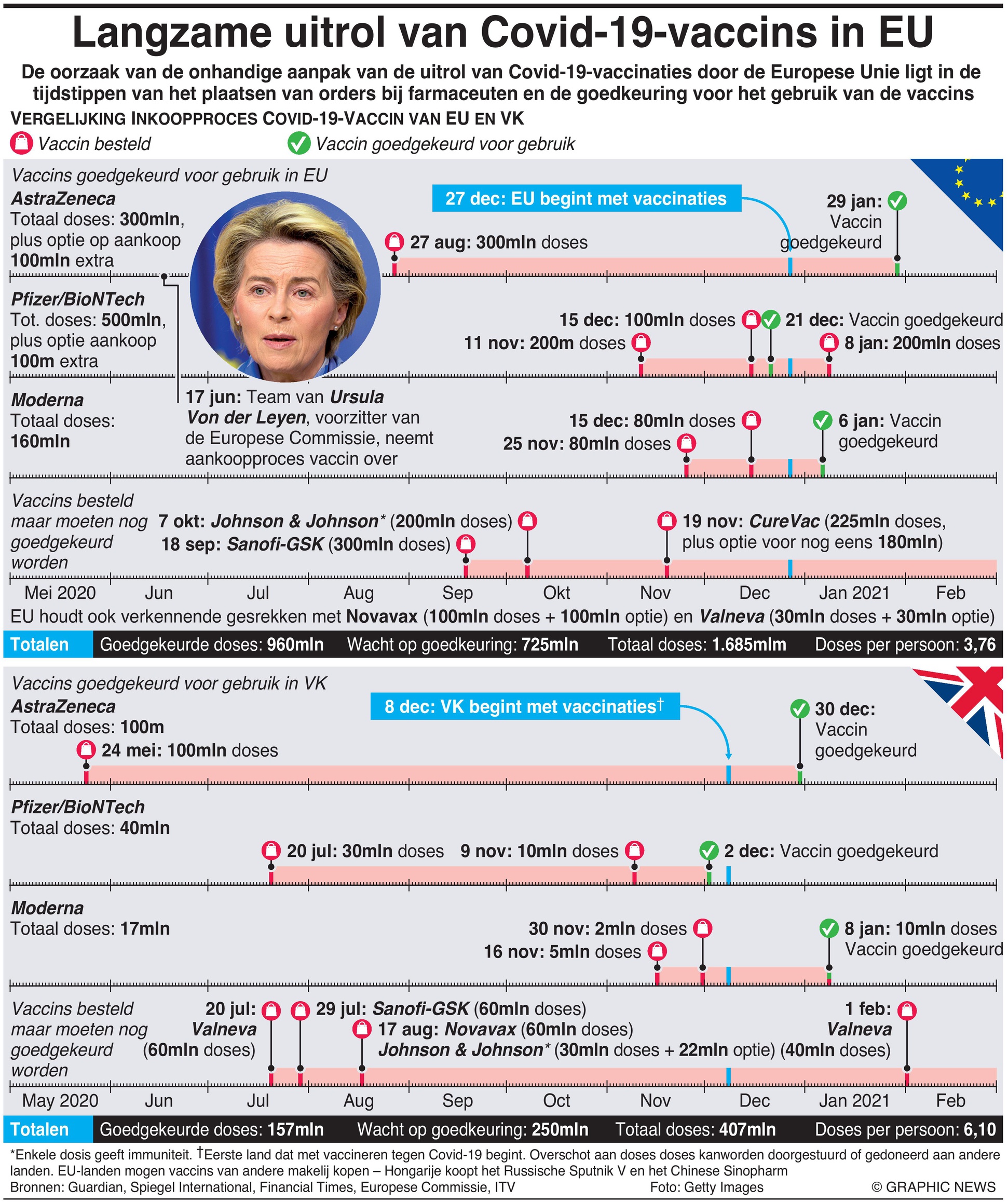

The European Union’s awkward handling of the Covid-19 vaccination rollout has its roots in when orders were placed with pharmaceutical companies and when approval was granted to use vaccines.

The European Union’s Covid-19 vaccination programme is struggling to get its hands on enough vaccine – trailing countries like Israel, the UK and United States. Worryingly, there seems no sign of the vaccination rate increasing anytime soon, unlike the UK, where rates have increased markedly in recent days.

A key failure is that the European Commission simply ordered too few vaccines too late. For example, it was too slow to order the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, even after it became the frontrunner, and member states hesitated to ask the Commission to order more.

Drug purchases were further delayed by disagreements over liability in case of negative side-effects on health from the vaccines, with the EU pushing for it to rest with pharmaceutical companies. This led to the rejection of early emergency authorisations as many EU member states were averse to such risks. Anti-vaccination movements may have compounded the pressures on politicians too.

The EU, with a population of nearly 450 million people, also found its funding wanting. Last year, it allocated €3.79 billion ($4.56 billion) for advance purchase agreements. By comparison, the U.S., with a smaller population of under 330 million people, pledged $18 billion.

The EU also chose to bargain with Big Pharma to achieve lower purchase prices, as if it had plenty of time on its hands, whereas other nations acted to expedite huge orders.

Further adding to the disarray is the slow speed to develop a strategy to increase production. More factories could have been mobilised as soon as possible to increase the total supply of vaccines, instead of waiting until this year to do so.

A recent furious spat with the UK has fuelled debate that the makers of the AstraZeneca vaccine may be breaching the terms of its contract with the EU, by not supplying enough vaccines to the bloc while maintaining good deliveries to the UK. But as the AstraZeneca CEO points out, the UK signed its contract three months before the EU did, and the UK factory also started operating earlier, increasing its capacity to supply.